History and Details About the Ghost Dance

Introduction

The Ohlone and Miwok people, the original inhabitants of the Bay Area, continue to assert their presence and advocate for their rights in the 21st century. This lesson delves into the contemporary issues these Indigenous communities face, focusing on their ongoing struggles for land rights, environmental justice, and accurate representation in media and education. Understanding these issues is crucial for appreciating the complex realities of Native Californians today and working towards a more just and equitable future.

Land Rights

Land is not simply a physical resource for Indigenous communities; it is intrinsically tied to their identity, spirituality, and cultural practices. The Ohlone and Miwok people, dispossessed of their ancestral lands through colonization and the Gold Rush, continue to fight for the recognition of their inherent rights to the land. This struggle takes many forms:

- Land Back Movements: These movements advocate for the return of ancestral lands to Indigenous stewardship. This can involve land purchases, legal challenges to existing ownership, and collaborations with conservation organizations to protect culturally significant areas.

- Federal Recognition: Many Ohlone and Miwok groups are still seeking federal recognition as sovereign tribes. This recognition would grant them greater autonomy and access to resources to support their communities and cultural revitalization efforts.

- Protection of Sacred Sites: Many places in the Bay Area hold deep spiritual significance for Native Californians. These sites are often threatened by development, vandalism, and desecration. Indigenous communities are actively working to protect these places, advocating for their preservation and access for ceremonial purposes.

Environmental Justice

Native Californians have a long history of environmental stewardship, and they are playing a vital role in contemporary environmental justice movements. They often face disproportionate impacts from environmental pollution and degradation, as industrial sites, landfills, and other polluting facilities are often located near their communities. Their efforts focus on:

- Climate Change: Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, such as sea-level rise, drought, and wildfires. They are advocating for climate action and sustainable practices that protect the environment and their cultural heritage.

- Water Rights: Access to clean water is essential for both cultural practices and everyday life. Native Californians are fighting to protect water sources from pollution and overuse, and to assert their rights to water resources.

- Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): Indigenous communities possess valuable knowledge about the environment and sustainable practices that have been passed down through generations. They are sharing this knowledge to promote ecological restoration and conservation efforts.

Representation in Media and Education

For too long, the stories and perspectives of Native Californians have been marginalized or misrepresented in mainstream media and education. This lack of accurate representation perpetuates stereotypes, erases Indigenous history, and contributes to cultural misunderstanding. Efforts to address this include:

- Reclaiming Narratives: Native communities are creating their own media, writing books and articles, and producing films that tell their stories from their own perspectives.

- Curriculum Reform: Indigenous educators and activists are working to ensure that school curricula accurately reflect the history and contributions of Native Californians, and that Native perspectives are included in all subjects.

- Challenging Stereotypes: Native people are speaking out against harmful stereotypes and misrepresentations in popular culture, advocating for more authentic and nuanced portrayals of Indigenous people.

Featured Voice: Corrina Gould - (Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone) Co-founder and Spokesperson for Indian People Organizing for Change (IPOC)

Corrina Gould Lifetime Achievement Award

Key Points from Corrina Gould's Work:

- Land Rematriation: Gould emphasizes the importance of returning land to Indigenous control, not just for symbolic reasons, but to enable the Ohlone people to practice their cultural traditions and revitalize their communities.

- Shellmound Protection: She has been a leading voice in the fight to protect shellmounds, ancient burial sites and cultural landmarks that are threatened by development.

- Decolonization: Gould advocates for decolonization, which involves dismantling the ongoing legacies of colonialism and recognizing the inherent sovereignty of Indigenous people.

- Intertribal Solidarity: She emphasizes the importance of building alliances and solidarity with other Indigenous communities and social justice movements.

End of Unit Exercises:

Short Answer (5 points each):

Choose ONE of the following questions and write a short answer for each with a paragraph or two:

- Explain the importance of land rights to Native Californians, and describe some of the specific ways they are working to reclaim their ancestral lands, such as land back movements, federal recognition efforts, and the protection of sacred sites.

- Discuss the connection between environmental justice and the cultural survival of Native communities in the Bay Area. Provide examples of how Native people are addressing environmental challenges and advocating for the protection of the land and water.

- Analyze the impact of inaccurate or incomplete representations of Native Americans in media and education. How do these representations perpetuate stereotypes and erase Indigenous history?

Essay (10 points):

Choose ONE of the following questions and write a well-developed essay response:

- Research and discuss a specific contemporary issue facing a Bay Area Native community, exploring their perspectives, challenges, and efforts to address the issue. Consider incorporating information from the featured voice or other contemporary Native sources.

- Reflect on how this unit has deepened your understanding of the history, culture, and contemporary experiences of Native Californians. How can you contribute to a more just and equitable future for these communities? Consider the role of allyship, advocacy, and education in supporting Indigenous rights and cultural revitalization.

Origins and Spread:

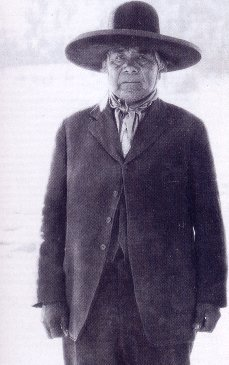

The Ghost Dance originated with the Paiute Prophet Wodziwob, a Paiute prophet in the late 19th century, who initiated an early version of the Ghost Dance movement (1869-1872). He preached that performing a ceremonial dance would bring back deceased Native Americans and restore their lands. Though his movement declined, it influenced the later Ghost Dance led by Wovoka in the 1890s, which became a major symbol of Native American resistance to U.S. expansion.

The 19 century Ghost Dance movement, which this course will be focusing on, is believed to have originated in 1889 with the Paiute prophet Wovoka, who received a vision foretelling a world where the dead would return, the buffalo herds would be restored, and the white settlers would disappear. The practice of the Ghost Dance spread rapidly across the western United States, particularly among the Great Plains tribes, who saw it as a means to revitalize their cultures and resist further encroachment on their sovereignty.

https://apps.lib.umich.edu/online-exhibits/exhibits/show/great-native-american-chiefs/group-of-native-american-chief/wovoka

Rituals and Beliefs:

The Ghost Dance typically involved a large group of participants, both men and women, dancing in a circle for days at a time. They wore specially designed "ghost shirts," believed to offer protection from the bullets of the white soldiers. The dancers entered trance-like states, seeking visions of the future and communicating with their ancestors.

Wounded Knee Massacre:

Prior to Wounded Knee, Lakota chief Sitting Bull fought Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer in 1876, which led to the defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn. This battle further spread anti-Native sentiments, as the news of Custer’s defeat “outraged many white Americans and confirmed their image of the Indians as wild and bloodthirsty.” (History.com* citation). While Sitting Bull wasn’t arrested, he was kept under watch as the U.S. government viewed him as a harsh adversary (Philbrick 2011). When Sitting Bull let Ghost dancers perform their ceremonies on his land, the government took action to prevent the Ghost Dance’s spread. In an attempt to arrest Chief Sitting Bull, the U.S. army met resistance from the local community, which ended with a U.S officer assassinating Sitting Bull (Dockstader 1977). This event sparked an event that saw other Lakota tribes headed to Pine Ridge in fear that the U.S. government may kill more chiefs. However, on the way to Pine Ridge, they were intercepted at Wounded Knee.

On December 29th, 1890, 500 U.S. soldiers gathered outside Wounded Knee, South Dakota where a Ghost Dance circle was forming. There, perhaps as revenge for the humiliation the 7th cavalry regiment received at Little Bighorn, soldiers began to fire on the gathering Lakota(“Wounded Knee: Massacre, Memorial & Battle - History.”). General James W. Forsyth asked for the Lakota to hand over their weapons. The leader of the Lakota, Chief Bigfoot, complied, but some warriors still held onto their weapons. One Lakota man refused to turn in his weapon - and set off the shot that would change the course of American history (Phillips 2006). As the Lakota warrior Turning Hawk describes, “[one of the Indian warriors] fired his gun, and of course, the firing of a gun must have been the breaking of a military rule of some sort, because immediately the soldiers returned fire, and indiscriminate killing followed” (Bateman 2018). Though there was an exchange of gunshots at first, the conflict soon turned into a one-sided massacre, with the soldiers chasing down women and children on horseback to complete their mission. The conflict was treated as a battle, and surviving soldiers were awarded medals of honor (“Wounded Knee: Massacre, Memorial & Battle - History.”).

https://www.history.com/news/wounded-knee-massacre-facts

The Wounded Knee Monument in the modern day.

https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/wounded-knee

Legacy and Resilience:

Despite its decline following the Wounded Knee Massacre, the Ghost Dance remains a powerful symbol of Native American resilience and the ongoing struggle for cultural preservation. Certain branches, such as the Kiowa Ghost Dance, would persevere through different forms for decades to come. The lessons of resilience and resistance taught by the Ghost Dance became an integral part of the perseverance of first nation individuals during a period of religious intolerance.

The events in 1890 at Wounded Knee stemmed from a systemic racist system that the federal government actively supported and encouraged. It took a genocide of over 200 indigenous natives and a full century of protest to finally break through into the American Imagination, demonstrating the extent of U.S. suppression of indigenous ideas. Though this same suppression still exists today, avid demonstrations to amend historical wrongs are in progress. Currently, Senators Warren and Merkley and Congressman Kahele are supporting a bill to rescind the medals of honor granted to those who fought at Wounded Knee (“Warren, Merkley, Kahele Lead Bicameral Letter Urging Biden to Rescind Medals of Honor Awarded to Soldiers who Perpetrated Wounded Knee Massacre”). Though this is little more than a sign of regret and a symbol of appeasement, it does demonstrate how this event shifted this country from ignorance of indigenous culture to finally recognizing its existence. In conclusion, the massacre of Wounded Knee must become a nationally recognized event and should be taught at all education levels. To stand on the right side of history, this country must take steps to recognize its wrongdoings and actively work to better its systems in the future. Both of these start with education as only through education can society work to improve a generation of racial and cultural expression.

There are no comments for now.